The Story of Betty Landes Wasser and her Family

by Luke Rothman

Copyright by Luke Rothman. Nothing may be reprinted without his express permission.

Today, January 27th, is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. This album a photo essay detailing my discovery that four of my grandmother’s relatives perished in the Lemberg Ghetto in 1943. I will eventually submit Pages of Testimony to Yad Vashem (The World Holocaust Remembrance Center) but I’m still working on finding out more details about their lives. I want them to be more than just names on a list.

Click on Photos to enlarge them..

Chapter 1.1

My grandmother Claire was born in 1909 on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. A few years after her death in 1998 I came across 25 pages of family history that she’d written in 1976. But her writing included only a few first names and zero last names, so it was difficult for me to put together a family tree. For example, she wrote:

"My grandmother and grandfather came here from a small town in Austria (Mosilifke). I know nothing about their ancestors. Her father must have been a widower and remarried because although she had no brothers and sisters, she did have a half - sister (whose daughter by the way was a dear childhood friend of mine and who died in her early twenties from Peritonitis, leaving her young husband behind).”

Who could that be? I knew Claire’s mother’s maiden name was Sadie Roller. But I would’ve needed to know Sadie’s mother’s maiden name, and that woman’s half-sister’s married name, and that half-sister’s daughter’s married name. Impossible.

Fortunately, as it turns out, there was someone else out there, searching in the opposite direction.

Photo Source: In June 2009 I went on a brief road trip around the Ukrainian parts of Bukovina and Galicia with a couple friends. My grandma’s maternal grandparents’ hometown of “Mosilifke” is the village of Mozolivka (?????????), Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine

Chapter 1.2

In 2008 while searching the genealogy website JewishGen, I came across a post that had been waiting for me since 1997:

“searching for DORA LANDES ROLLER, another daughter of Chaim and Chaya Landes. She had children named Joe, Morris, Jack?, and possibly a daughter.”

I knew those names! My grandmother spoke with pride of her uncle Joseph G. Roller, the successful businessman who arrived on Ellis Island in 1903 with his mom and a couple siblings and $6 among them.

Some of Joe’s siblings were Morris and Jack and Sadie (Claire’s mother), so I wrote to the author of the 1997 post. Helen May wrote back immediately, and we filled in some blanks to confirm the connection. Helen’s grandmother - and namesake - was the much-younger sister of Claire’s grandmother Dora Roller.

Photo Source: Years ago I bought this group of fur tags on eBay from someone in Kansas who probably found them in an attic. From my grandma’s stories, it’s my understanding that trappers and hunters would send their furs to people like Joe, who stretched and cut them to resell to coat makers etc. At the time, fur was cheap and woven textiles were expensive, so fur was big business.

Chapter 1.3

Helen and I exchanged stories and family lore, and at the end of one email she wrote:

"p.s. Wait!!!!! I have more….. I assume your grandmother is no longer alive….. if she was I would ask her the name of the daughter of the half sister……. My grandmother, Helen Landes also had a daughter, Carol (my aunt and my father's sister) who died of peritonitis in her early 20's leaving a husband!!!. She died around 1937. How old was your grandmother then? Where did they live? My father and his family lived first on the lower East side of NY and then in Washington Heights. My Aunt's name was Carol Noschkes Rimai."

Carol was Claire’s “dear childhood friend.” Helen sent me a few photos of her aunt, and while there are no photos of Carol and Claire together, I was pleased to find out that Carol is remembered beyond the few anecdotes my grandmother jotted down decades ago.

Carol and Claire had the same Hebrew name: ??? or Chaya, which means “Life”.

Chapter 1.4

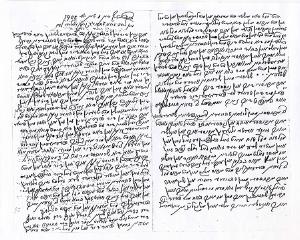

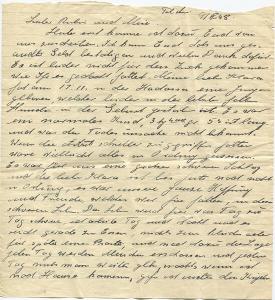

My great-great-great grandmother Chaya Landes - the mother of Betty and Dora and the elder Helen - died sometime before 1906. Her widow Chaim Landes sent this letter from Buczacz, Austria-Hungary to his daughter Helen in NYC on the occasion of her marriage in 1908. It is in Yiddish, and here are parts of the translation:

Buczacz 1 June 1908 To daughter Ettie from father. My beloved, dearest, sweet child Ettiya, my soul. My dear child, I cannot describe to you how much pleasure your dear letter brought to me. But I am alone and I fear that God does not find me worthy enough to come to the wedding. As you know, I have no means to be with you my dear children. I always hoped dear children that I would be able to be at your wedding because you were always my best, and my most loved child. But dear, what can I do? ...and during the night I lie in bed, my eyes full of tears, my dear child. You think that I have forgotten you... I didn't forget you because you are my best child and my dearest child. My dear child, my heart longs so for you, but my strength is dwindling bitterly. ...Dear child, this letter is not written with ink but with tears, yes, and I hope that God gives me the strength to withstand it ... I conclude my writing again with mazal tov. I send you greetings and kisses many thousands of times from me, your dear and unforgettable father who is hoping to see you at least once more. Chaim Landes.

Chaim Landes never saw Helen again, and he died in December, 1913.

Chapter 2.1

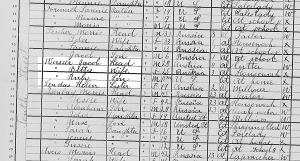

Let me return to the first part of Helen May’s 1997 post, which I skipped: "I am searching for descendants of my gmother's sisters: "Searching for Betty LANDES, daughter of Chaim Landes of Buczacz and her descendants. She was married here in the US to someone named WASSER. "Mr. WASSER had a son… named Ruby who married a nurse and possibly lives in Louisiana." Helen was told this information by her uncle Monroe (he was Carol’s younger brother, and Ruby was their cousin). My grandma, Claire, wrote that her grandmother had one sister, not two. Who is Betty? I did a little research: in the 1905 New York State Census, she and her husband Jacob had a baby son Ruby, and Betty’s sister Helen Landes lived with them. My grandmother knew Helen, but did she know the others? Why didn’t she mention them in her writing?

Source: 1905 New York State Census

Chapter 2.2

Ruby and his sisters would’ve been over 100 years old when I was doing research in 2008, so they were almost certainly deceased, but perhaps they had children or grandchildren…? Unfortunately I could find no record of the Wasser family after 1910. They'd disappeared.

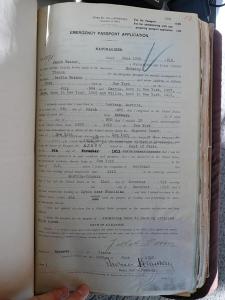

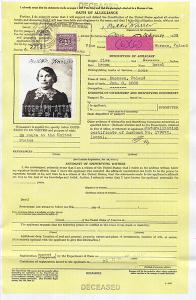

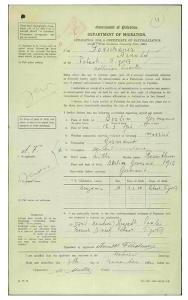

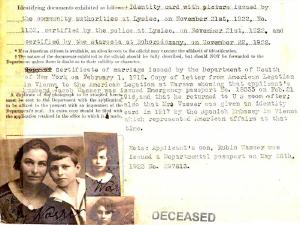

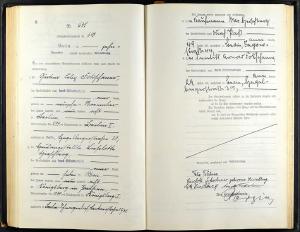

In a giant old tome at the National Archives II in College Park, MD, I found this Emergency Passport Application made by Jacob Wasser at the American Embassy in Vienna during the summer of 1915. As it turns out, the family had left New York in 1912 and returned to the Wasser family farm in Lysiec, Galicia (modern-day ??????, Ukraine).

In 1914 the surrounding region was conquered by the Russian Army, and by the summer of 1915 Austro-Hungarian forces were pushing them back. The Wasser family wanted to return to New York, but their youngest son was born with clubfoot. They hoped to have him treated by Vienna’s famous Dr. Adolf Lorenz, who pioneered “bloodless surgery” for several congenital birth defects including clubfoot (I’ve contacted the Adolf Lorenz Society several times over the past decade to ask about Willie Wasser’s records, but I’ve never received a response).

This June 1915 passport application was “for the purpose of remaining here to have my crippled child cured.”

Source: The JewishGen database “Emergency Passport Applications at Various U.S. Consular Posts,1915-1926”, which has a fascinating description of these records. Here is an excerpt: “The Emergency Passport had to be renewed annually and, during the war, this became difficult as U.S. Consular offices closed in many countries. A family caught in Europe for the duration of the war, may have applied multiple times in multiple locations, reflecting the chaos and disruption that people were experiencing. The Emergency Passport was also used by men who were U.S. citizens who, at the outbreak of war… had, effectively, returned to Europe to live as U.S. residents abroad. When they also were stuck in Europe for the duration of the war, they had to apply for an Emergency Passport when their passports expired and then every year thereafter.”

Chapter 2.3

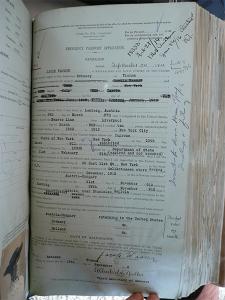

Jacob’s third passport application was only for himself: he returned to New York in the fall of 1916 with the hope of earning money to support his family. A decade earlier his profession was “fur cutter”, and on this passport application he said he was a “delicatessen store keeper”. But he was soon working as a bartender for his friend George Greenberger in Norwich, CT. I suppose he was doing his best to maximize

The US entered the war in 1917, and by June 12th, Betty was described in one letter as “quite destitute.” At one point, she and the children lived with Jacob’s brother Osias in Vienna. The US Embassy had closed, so Betty asked the neutral Royal Spanish Embassy in Vienna to ask the State Department to inform her husband that “she is in urgent need of funds for the maintenance of herself and her four children” in addition to “the fact that the youngest child has undergone an operation and is therefore in need of expert medical attention.” She also needed copies of the children’s birth certificates to enroll them in local schools.

Just six weeks later Betty requested that Jacob send money to buy steamship tickets to return to the United States, and she asked for copies of his naturalization certificate and once again asked for the children’s birth certificates. She wrote that “the amount of $200, even if received, would not be sufficient to cover the expense” to return to the United States. Her honesty was later used against her.

[I was curious about that signature at the end: Allen Welsh Dulles, age 23, later became director of the CIA. The airport was named after his more famous brother John Foster Dulles.]

Chapter 2.4

July 30th: the State Department told Jacob they were “accepting deposits for transmission to Americans residing in Austria-Hungary only for their immediate relief and transportation to the United States.” They would not transmit money to an enemy nation for any other reason (there was an exception when “evidence of physical inability to leave is proven”).

August 29th: Jacob received another letter from the State Department informing him that they were “willing to give consideration to a request from you for the transmission to your wife of such an amount of money as will reasonable meet her immediate requirements and pay the passage of herself and the children to the United States.”

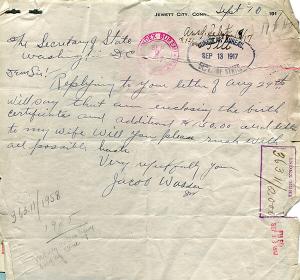

September 10th: Jacob sent this letter with money orders for $50 and $100, in addition to the children’s birth certificates. Betty had said $200 would not even be sufficient, so perhaps Jacob sent as much as he could afford. Or maybe Betty had other sources that would make up the difference.

Source for chapters 8-11: I scanned these documents in person at NARA-II in College Park, MD. The JewishGen page “Jewish Names in Selected U.S. State Department Files (RG59)” explains how to access files in this collection.

Chapter 2.5

Nine days later, on September 19th, 1917, Jacob received another letter from the State Department:

“As the Department is not accepting deposits for transmission to American citizens residing in Austria except for their immediate relief and transportation to the United States or to some neutral country and as the $150 enclosed with your communication under acknowledgement does not seem sufficient to cover the necessary transportation expenses of your wife and children your money orders are returned herewith. The Department also returns the letter addressed to your wife and informs you that it cannot be of assistance in transmitting in the official pouches mail addressed to private persons residing abroad.

“Enclosures: Two money orders and Original Letters.”

And they also returned the birth certificates, which - to this day - are in a box on a shelf in a giant building in Maryland.

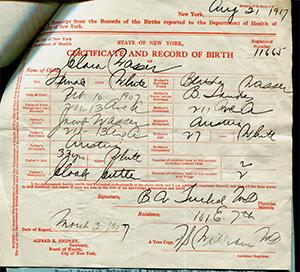

When I came across these documents at the National Archives II, I realized that “Carrie” from the 1910 census was born Clara. Just like my grandmother. Claire and Carol and “Carrie” were all named for Chaya Landes.

Chapter 2.6

Armistice Day was November 11th, 1918. Three days later, the Royal Spanish Embassy in Vienna sent a few “lists of American citizens in Austria-Hungary” to the State Department. Betty and her children were on the list of several hundred people described as those who:

“have been cut off from the husband and father for several years, know nothing of his financial condition, and, since the sums remitted are manifestly inadequate to meet the expense of the journey under present conditions, are afraid that further funds cannot be sent to them in Switzerland or at other places en route, and that they will be left friendless and penniless in a strange country.

“…It may be added, however, that nearly all persons of this category belong to the peasant or laboring class, that they have all their lives been engaged in agricultural or other manual labor, and that as long as they remain among friends or acquaintances they are able to find employment remunerative enough to enable them to eke out an existence.”

Those last words struck me: “?????? ?????? ???? ??????????????????.”

Chapter 2.7

When the war “ended” on 11/11/1918, the combatants didn’t simply put down their guns, shake hands, and go back to their old lives. In fact, the fighting continued through July 1919 in eastern Galicia and other areas (this was called the Polish–Ukrainian War).

Jacob wrote several letters to the State Department to ask for assistance finding his family in eastern Galicia.

Late December: State Department suggests he apply “to War Trade Board with evidence of Am. Citizenship re transmission of funds to family in Galicia.”

February: Jacob “States that his wife has left Galicia and is en route for Holland which makes it impossible to send funds but asks for passport to go to Holland to bring them back.”

March 11th: Jacob “asks if the Department can trace his relatives, so that he might send them funds.

March 18th: In response to his last letter, the State Department “has received your letter asking its aid in obtaining information concerning the whereabouts and welfare of your family who, when last heard from, were living in Lysic, Galicia, stating if you submit documentary evidence of your American Citizenship, Department will consider this matter.”

By this point I’ve lost track of how many times he was asked to prove his citizenship. Up until his death five weeks later, he was probably still trying to find his family.

The quotations above are from index cards in the 1910-1963 Name Index of the Department of State Central Decimal Files Record Group 59, at NARA-II in College Park.

Chapter 3.1

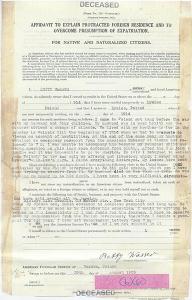

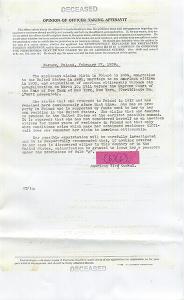

Betty kept trying to return to New York. She submitted a passport application in 1923 and was required to fill out this form "to overcome presumption of expatriation” since she had been outside of the US for many years.

The “Opinion of Officer Taking Affidavit” stated: “In my opinion, a presumption of expatriation has arisen against the affiant for not having declared her intention to retain her American citizenship within a year of her husband’s death. She declares that she cannot return to the United States till she receives compensation from the Polish Government for losses incurred during the war, and I am more than

Betty was likely unaware of Jacob’s 1919 death for months after the fact (or perhaps years: on this 1923 document she states that he died in 1921). And yet now she would be presumed expatriated because she hadn’t declared her intention to retain her American citizenship within one year of becoming a widow.

Source: In 2009 I requested Betty’s passport records from the State Department.

Chapter 3.2

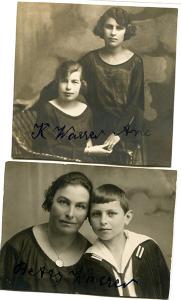

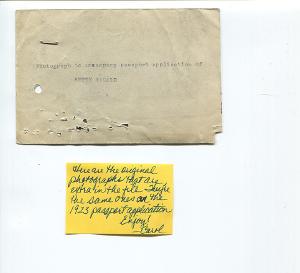

My 2009 request for passport records was assigned to an incredibly helpful specialist whose name happened to be Carol. She wrote, “I'm so glad we were able to locate her records and to find those extra photographs still attached.”

During one of our many phone calls she explained the State Department's informal policy of returning personal effects to families whenever possible. Since no one had ever requested these records, Carol sent me the original envelope of photos that Betty submitted with her 1923 passport application. I told her I’d keep them safe, in case I ever found any descendants.

Carol said I was lucky they were never destroyed. These may be the only extant photos of Willie and Anna Wasser.

Chapter 3.3

The tiny envelope, punctured with lots of little holes from old staples that’d been removed, remained in

Carol wrote, “Apparently, they would have been the photos to use on the passport had it been issued. Very glad your family now has them.”

I have yet to find any documents more recent than 1923 which mention the youngest son, Willie Wasser (born either 7 Dec 1913 or 13 Dec 1913 in either Lemberg or Lysiec). His story ends here, with a giant question mark.

Chapter 3.4

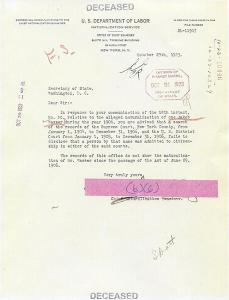

This letter from the Department of Labor is the reason Betty’s passport application was rejected: her citizenship (derived from her deceased husband’s citizenship) could not be verified. Betty had told them her husband was naturalized in New York in 1906; they searched the records, found nothing, and denied the application.

But she mixed up the year of his Declaration of Intention with the year of his Certificate of Naturalization, which means they should’ve been looking at records from 1911. This occurred despite the fact that her husband’s citizenship had already been verified when his 1916 passport was issued.

Given the strong anti-immigration sentiment in 1920s America, I suspect Betty’s difficulties were the norm, not the exception.

Chapter 3.5

Betty’s eldest son Reuben was not a minor, so he applied for a passport separately in 1923 and was approved, but he remained in Europe. In 1925 he applied for a renewal, explaining that “in 1921 I began to study in the Technical school at Bielsk. I hope to finish the school this year and I intend to go to Vienna or Charlottenburg in order to practice in a mechanical laboratory. I think that my studies will last about six years; after this time I intend to return to the United States”.

This “Opinion of Officer Taking Affidavit” stated that Reuben was not entitled to a passport, unless he were to return to the United States immediately. Perhaps he took his chances: a new passport was issued two years later, in the summer of 1927. The reference on his application was a chemical engineer from Austria-Hungary, employed by Standard Oil of Louisiana.

Various records show that after living in Louisiana, Reuben moved to NYC and married a nurse named Alice in 1935. This confirmed the first detail I’d ever heard about him: Helen May’s uncle had told her about “Ruby who married a nurse and possibly lives in Louisiana.”

Chapter 4.1

Betty gave up on returning to the US after being rejected in 1923. But then in February of 1939 she applied for a passport again, and she included proof of her husband’s naturalization, which she’d been unable to find for the previous application. She was provisionally rejected yet again, but the State Department finally declared that if Betty were to make “definite arrangements to return to the United States for permanent residence… a limited service passport may be issued.”

This willingness to issue a passport surprised me, because the “Opinion of Officer Taking Affidavit” was: “She claims that she desires to proceed to the United States at the earliest possible moment. It is apparent that she has not considered herself as an American citizen for these years of residence in Poland and that only when conditions arise which make her continued residence difficult does she remember her claim to American citizenship.”

On the other hand, her “Affidavit By Naturalized American to Overcome Presumption of Noncitizenship” included an interesting note at the end of her personal statement: “Applicant’s independent statement made in English.” How did she still speak English? She was in her 50s, and she’d only lived in NYC between the ages of 20-30. During that first decade of the 20th century, Jews on the Lower East Side could’ve gotten along fine with just Yiddish. Not only did Betty learn English, but she still spoke it 30 years later. Impressive.

Chapter 4.2

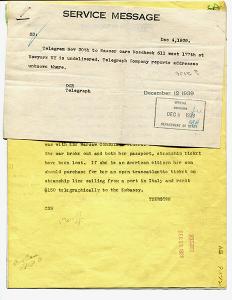

In the fall of 1939 Poland was invaded, divided, and annexed by Germany and the USSR. In November, Betty was still trying to make arrangements to travel to New York. She wrote to her son Reuben, c/o Noschkes, at 611 West 177th Street, New York.

This same address was on the 1935 marriage certificate of my grandma’s cousin Carol, who had died in 1936 “from Peritonitis, leaving her young husband behind.” And the address was also on the 1937 death certificate of Betty’s sister Helen Landes Noschkes. By the fall of ’39 the remaining family - just two brothers - had moved. The telegram was marked “undelivered” in December.

Chapter 4.3

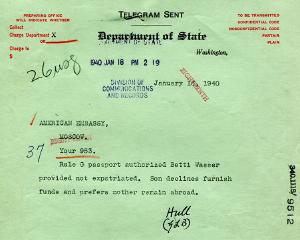

Within a few weeks the State Department managed to locate and contact Reuben. In January 1940 Betty received the attached brief telegram with no explanation.

I reviewed the internal State Department correspondence - which Betty never saw – and it goes into more detail about their communication with Reuben: he "has heard from her right along and he states that she never mentioned in any of her letters about returning to America… he believes Mrs. Wasser is much better off in Poland than she would be here, living alone, and does not care to advance any money for transportation.” I have no letters or direct quotes from Reuben. Please keep in mind that hindsight is 20/20. It is completely reasonable that Reuben thought his mother would be better off staying where she was. No one in 1939 foresaw what was about to happen.

Reuben soon realized the gravity of the situation in Europe and changed his mind. He sent funds, but it was too late. For several years the money was “in the list of trust funds held by the American Embassy at Kuybyshev[*] for payment of Passport and Visa fees, and travel expenses to the US on behalf of Betti Wasser, a person believed to be residing within enemy-occupied territories.”

*Modern-day Samara, Russia was called Kuybyshev at the time. For several years during WWII it was the backup capital of the Soviet Union, in case Moscow were to fall to the invading Germans.

Chapter 4.4

I could imagine that for the rest of his life Reuben was haunted by his delay in sending funds. He was an extremely accomplished and admirable person, and I don’t want to leave you - my several readers – thinking that he abandoned his mother. My impression is that he did what he thought was best, regretted it, and reversed course soon after.

I’d like to provide a little more background on the rest of his life. One of his relatives on the Wasser side told me this:

"Reuben did return to Europe from the US when he was young, though I don’t know the dates or how old he was. …he left Europe in the 20s and took jobs in both Texas and Louisiana. …[He] then moved to New Jersey. When my mother and her parents moved to New York in 1945, my grandmother (who would have been Reuben’s first cousin) got in touch with him and we then were in reasonable contact with them until they moved to Florida and afterwards. "My mother knows nothing about Reuben’s mother’s family or any of his siblings. As I said, those were not topics he talked about to my recollection. "He and Alice (who was a lovely person—she was a registered nurse who worked in the tenements in NYC, was a tremendous seamstress and made absolutely delicious homemade bread) never had any children as you probably know. They liked children very much, though, and I remember they had a cupboard full of board games and puzzles in their house that I used to amuse myself with when my mother and I would stop overnight with them on our way to and from vacations in Massachusetts. Reuben was an excellent cook too—he tended to do the meat—and grew wonderful tomatoes."

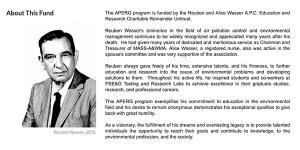

Reuben Wasser passed away in Florida in 1982, followed by his wife Alice in 1997. They left their assets to this charitable trust which “provides financial support that will enable doctoral students and post-doctoral scientists to pursue research careers in the environmental field, and in particular to those scientists interested in issues related to air pollution, air quality, and the atmosphere.” The grants are "$25,000 each with a total of two to five awards made per year. The APERG program has given out more than $1,250,000 to date and expects to continue generous support for many years to come."

Chapter 4.5

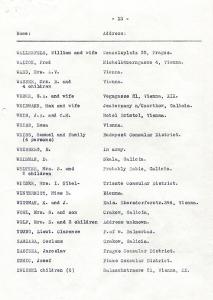

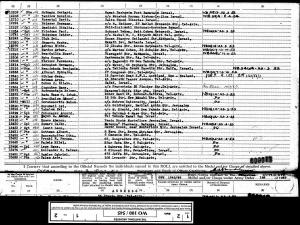

Since Betty was described in the early 1940s as “a person believed to be residing within enemy-occupied territories,” I went to The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum here in DC. They have a copy of the Central Name Index from Arolsen Archives (formerly ITS), which “includes 50 million reference cards on the fate of 17.5 million people.”

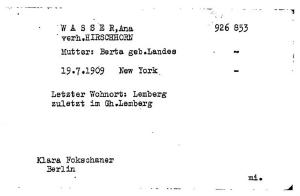

At the USHMM, I searched the Central Name Index and found ten cards like this. It turns out I’m not the only person who ever tried to find out the fate of Betty Wasser and her family. In 1959, 1964, and 1984, ITS was asked for any information on these people:

1) Bertha Wasser, née Landes, born 8 Jan 1884

2) Ana/Anda Hirschhorn, née Wasser, born 19 Jul 1908 in New York (mother Bertha née Landes)

3) Dr. Jacob Hirschhorn, husband of Ana née Wasser, born 19 Mar 1904 in Lemberg

4) Krystyna Hirschhorn, daughter of Jacob and Ana née Wasser, born 6 Oct 1936 in Lemberg

Finding these cards was an emotional mini-rollercoaster, over the course of about one minute. First I learned that Ana had a husband and a daughter! But then I remembered these are missing person inquiries from the Lemberg Ghetto. On the other hand, the daughter was born in 1936 - what if she survived, maybe in hiding, and is alive, maybe under a different name?

I quickly googled the Lemberg Ghetto and realized it was one of the worst. Well over 100,000 Jews were forced into this ghetto, and by the time it was liberated by the Red Army in the summer of 1944, only a

I looked closer at the names and dates on the ten cards, which all had slight variations. In 1959 one inquiry was made for Betty Wasser, and that card didn’t list the name of the person inquiring. It was submitted through the Red Cross in Geneva, and it was marked “usa” on the edge. Maybe Reuben inquired in 1959? Or was “usa” simply Betty’s citizenship?

The 1964 inquiries were made by a woman in Berlin named Klara Fokschaner. The 1984 inquiries were from the Red Cross in Berlin, so they were probably from her as well.

Every index card ends with some variation of “Last message: from the Lemberg Ghetto”. Whoever submitted these inquiries had been in contact with Betty, Ana, Jacob, and Krystyna until perhaps 1943. I already knew that Reuben had never talked about his mother and siblings, and he had no children or estate or documents that might still exist.

But maybe I could find Klara Fokschaner.

Chapter 5.1

It was depressing - albeit expected - to learn that Betty and her family were almost certainly killed in the Holocaust. And to imagine the short life of her young granddaughter Krystyna, who probably never saw her 7th birthday, is heartbreaking. So I wondered about this Klara Fokschaner, a person who was alive at least through 1984 - in Berlin, of all places! Could Klara Fokschaner be the married, Germanized name of Clara Wasser? Maybe I had long-lost relatives in Berlin who could tell me more about Betty, Ana, Jacob, and Krystyna.

I wrote to the ITS to request copies of the requests made by Klara Fokschaner, in hopes of discovering her connection to Betty’s family. ITS quickly confirmed Reuben had not made the 1959 request, but further details would take months to find.

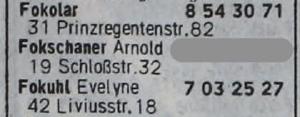

In the meantime, I did a little digging to see what I could discover on my own. In the summer of 2009, I looked at old phonebooks from Berlin and found that Arnold Fokschaner lived at the same address and had the same phone number for many years. This address is in the heart of what was the British Sector of West Berlin.

No one else named Fokschaner was ever listed in Berlin, so I was pretty sure Arnold was Klara's husband.

Starting in the late 1990s, Arnold Fokschaner was no longer listed, but Charlotte S___ lived at the same address and had the same phone number. Could this be Arnold and Klara’s daughter?

I asked a friend with very rusty German (he’d lived there as a kid) if we could get together and call Charlotte S___ while he interpreted. She was an older woman who was quite helpful and patient with my friend’s basic German. We immediately learned that she was not, in fact, the daughter of Klara Fokschaner. But she recognized the name of the previous tenant of the apartment, and told us what she’d learned over the years from other neighbors in the building: Klara Fokschaner was American, and maybe she worked for the American military. Her husband had died many years before. She had a son - maybe he was an adopted son, and something about Palestine? - but the son died a few years after the mother, possibly of a heart condition. He’d never married.

By this point I was about 99% sure that Klara Fokschaner was Clara Wasser. While the call was extremely helpful, it was disappointing on two points: Charlotte was not Klara’s daughter, and Klara did have a son but he’d died; there were no other family members.

Chapter 5.2

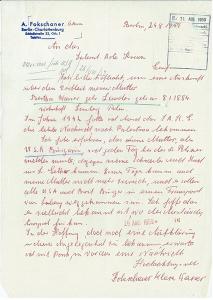

In June 2010, a year after first contacting ITS, a long-anticipated piece of mail arrived from Bad Arolsen, Germany. The envelope included copies of Klara Fokschaner’s 1959 and 1964 tracing inquiries.

These letters confirmed that Klara Fokschaner of Berlin was born Clara Wasser in New York.

The 1959 inquiry – which mentions Betty’s US citizenship – reads:

A Fokschaner

Berlin – Chalottenburg

Schloßstraße 32, Gth. 1

Phone ______________

Berlin, August 24, 1959

To the International Red Cross

I respectfully ask you for some information about the whereabouts of my mother

Bertha Wasser, born Landes, born January 8, 1884.

Resident of Lemberg, Poland.

In 1942, I received the last note via the International Red Cross Committee to Palestine.

I found out that my mother, as a US citizen, had to report to the police every day; my sister and (her) child were brought to ‘L. Letho’ (?). One day, my mother didn’t return and apparently all US and British citizens were taken in a transport from Lemberg. I hope that it is known where the transport of foreigners was brought.

Hoping to receive some clarification in this matter; I am waiting for a notice with thanks in advance.

Yours sincerely,

Fokschaner Klara Wasser

Chapter 5.3

Prior to 1934, American women who married foreigners automatically lost their US citizenship. Because of that policy, Anna was likely not an American citizen in 1942 when “all US and British citizens were taken in a transport from Lemberg” (quoted from Klara’s 1959 letter). Maybe Klara thought Ana’s family could’ve survived (although that doesn’t explain the lack of a tracing inquiry; it’s possible she took other steps like publishing missing person listings in newspapers in the 1950s).

But by 1964, perhaps she’d learned more about the general fate of those who were in the Lemberg Ghetto, because her later request covers Betty, Ana, Jacob, and Krystyna. A translation is below.

Dear Sirs!

Please allow me to ask you respectfully if you are able to tell me the whereabouts of my family members.

- Mother: Berta Wasser, born Landes, born Jan 8, 1880 in Buczacz. Last known residence: Lemberg, ul. Panienska 43. During the German occupation of Lemberg, my mother, a US citizen, was asked to report to the police twice a day. One day she didn’t return home. This happened in 1942 or 1943.

- Sister: Anda Hirschhorn, born Wasser, born July 19, 1909 in New York. Last known residence: see above, point 1. She was last seen in the Lemberg Ghetto.

- Brother-in-Law: Dr. Laywer Jacob Hirschhorn, born March 19, 1904 in Lemberg. Last known residence: see above. Dr. Hirschhorn went one day to look for his mother-in-law and did not return from this trip.

- Daughter of the Hirschhorns: Krystyna Hirschhorn, born October 6, 1936 in Lemberg; last seen with her mother in the Lemberg Ghetto.

I would be very thankful if you could provide some small assistance to find any possible survivors of my family and let me know if you have any documentation about to which extermination camp they may have been brought.

With best thanks for your efforts in advance

Yours respectfully,

Klara Fokschaner

Chapter 5.4

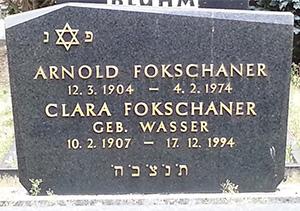

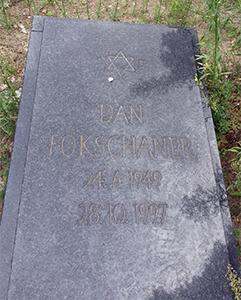

With the help of the ITS researcher assigned to my case, I obtained a death certificate showing that Klara had died in 1994, and was buried at the cemetery Jüdischen Friedhof am Scholzplatz, Heerstrasse 141, 14055 Berlin - Charlottenburg.

It’s hard to give up when you’ve come this far. But German privacy laws are strict, and Jewish cemeteries in Germany are tight on privacy and security, so I couldn’t find any name or death or cemetery records for this son. Years later, in the summer of 2013, another friend was planning to be in Berlin, so I asked him to go on a little adventure out to the cemetery. He took this photo and the next one, which gave me some dates, some closure, and a name.

It’s still hard to believe that my grandmother had a cousin of the same age and name who was also born in NYC, who somehow ended up back in Europe and survived WWII and settled in Berlin and lived until 1994. How did she get there? What's her story?

Chapter 5.5

Anyone familiar with Jewish cemeteries will notice the stone placed on this grave. Is it deliberate, placed there by a friend? Or is it simply a piece of gravel from the next grave, kicked up here by a weed whacker? Surely there are people in Berlin who knew this man who lived from 1949-1997. If he were still alive, he’d be younger than my parents! But I’ve never made any progress finding any acquaintances of his in Berlin.

I tried what I could: I even joined a German Jewish Genealogy listserv and wrote to the members to ask for any contacts in Berlin, or anyone who may have known the Fokschaner family. A man named Peter Freeman* responded to me and wrote “I knew an elderly gentleman of that unusual name here in London… whose widow and progeny are still living.”

Peter contacted the widow of the man named [___] Fokschaner, and she said she’d be happy to try to answer questions I might have about her husband’s relatives. She wrote:

“Good to meet you and the story is very interesting. The only other Fokschaner that I know of is ____ Fokschaner who lives in [Israel] and he would have longer memories of everyone, I remember that they were supporting an aunt in Dusseldorf whose name was ____ who has also since died.”

So then I reached out to her deceased husband’s cousin in Israel, who was also very helpful, and he wrote: “I lived in Palestine from practically age 0 (1939) and must admit I cannot recall having heard my parents (Father's name was ____) mention an Arnold Fokschaner.” He asked a few other relatives, but none had ever heard of Arnold.

Now that I’d contacted the several Fokschaners in the world and found no additional information on Arnold, I thought I might be done with this line of research. Maybe I’d never learn anything else about Klara or her family members.

* [After putting this photo essay online Wednesday, I was sure I’d hear from Peter right away; we’re Facebook friends and had occasionally been in contact over the years. I’m saddened to see that he passed away just a few months ago. I know he would’ve loved seeing this story and being a part of it.]

Chapter 6.1

I thought I’d hit a dead end, with my last best hope being a listing of Arnold Fokschaner’s name in a record group titled “German Jewish Refugees Who Emigrated to Palestine”. Held at the Israel State Archives (ISA), the collection contains files on 38,370 German residents who emigrated to Palestine between 1933-1948.

When I first contacted the ISA in 2010, they told me “regrettably the file is in a very bad physical condition” and could not be viewed, even if I were to go in person. In 2015 I heard about an upcoming digitization project that would cover many record groups including this one, so I contacted ISA again. They said the file was lost. Not just the file, but the entire record group (which would take up hundreds of filing cabinets). Perhaps there was miscommunication - that had to be wrong. But I knew the digitization would take years, so I occasionally searched online for updates.

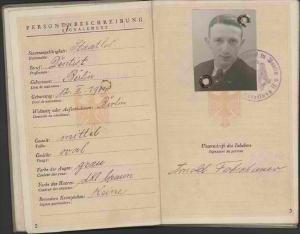

In 2019, I was excited to find that the entire collection had been digitized and placed online! This is one of the 42 pages of Arnold Fokschaner’s file: his German passport, issued in Berlin in 1935. Nationality: Stateless.

Chapter 6.2

Arnold Fokschaner was married to Lilli Rosenblum when he left Berlin. Given the matching date of birth and the rarity of his name, I knew this was the correct person, which meant Klara Wasser wasn’t his first wife. In the 42-page file from the Israel State Archives I found mention of a son Benjamin, born in 1938 to Lilli and Arnold. Perhaps I could find this man, and maybe he would know something about his father’s second wife…?

I contacted a source in Israel who wrote the following:

"I see no one named Benjamin nor any Fokschaner whose father is Benjamin. Perhaps the surname was changed. I see one Benjamin born 13 March 1938 and his father is Arnold, but his surname is Herbst. …he was living in Eilat. There is a woman named Anugah (b. 1939) at the same address and there is a woman named Orit (b. 1969) with no address. "

Ten minutes later, I’d tracked down the Herbst family (in California, of all places!) and found them on Facebook. But this was a dilemma. What if Benny Herbst’s parents had divorced when he was a baby, and his mother remarried and gave Benny his stepfather’s last name? What if he never even knew about Arnold Fokschaner? Contacting an octogenarian - who I’m not even related to - and giving him this news made me feel uneasy.

After some debate, I contacted him. I’d come this far and had no other leads. His response was a relief:

hi Luke. just read your txt on msgr. no shock, just surprise and interest. I wish to answer in more details what ever little I know on Klara. let's communicate by email: b____@gmail.com I will have your email when you send. have a wonderful 4th. D.C will have a big celebration. shalom. Benny.

[Ironically, months later I was organizing some files and asked Benny for help with a Hebrew translation. Years ago I’d saved some document off the internet with the rare surname Fokschaner (??????) but I’d never translated the whole thing. Benny told me “The list has to do with name changes of variety of persons living in Eilat at that time Dec1963. I did live in Eilat at that time. It shows the name Fokschaner

Chapter 6.3

Benny is very tech-savvy (he’s an electrical engineer by training; he and his wife founded their own tech company in the 1970s). Within a couple days he had scanned and sent me all of the dozen or so documents pertaining to his birth father that he kept in a file.

Benny’s parents divorced when he was a toddler, and his father Arnold met Clara Wasser while serving in the British Military, probably in Egypt. "The picture of Clara, Arnold and myself on the Board Walk in Tel Aviv is the first time that I met them for few hours. This was around 1943. its likely that they were already married at that time."

His mother also remarried; he mostly lost touch with Arnold and Klara after they moved to Berlin a few years later.

Neither Benny nor I have any information on Klara’s life between WWI and 1943. Someday I’d like to learn where she lived all those years, when she learned to speak German, how she ended up in Palestine, and how she ended up in the British military. It’s just such a completely different path from her mother and her sister’s family, who all stayed in Galicia until the very end. Not to mention her brother Reuben, whose Jewish-American life was more typical (lived in New Jersey, retired to Florida).

Chapter 6.4

Benny told me that Arnold and Klara were in the British military, but Charlotte S___ in Berlin said Klara was in the American military. I’d never found any American military records for her, but I’d never looked for any British records.

I did a little searching, and I found one document from the British National Archives. The collection is “UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, Palestine 1945-1948”, and the date is 3 July 1951. It lists “Arnold Fokscaner [sic]” about 2/3 down. So Klara was probably enlisted in the same service, but I’m not sure how to find her enlistment and other records.

Chapter 6.5

Dan Fokschaner was born to parents Arnold and Klara in 1949, and the family moved to Berlin - where Arnold was from - in the early 1950s. Benny and his birth father never had a relationship, and he only met Klara that one time on the boardwalk in Tel Aviv. He never met Dan.

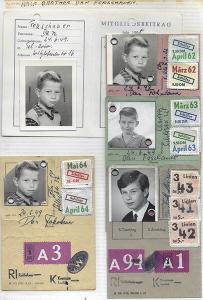

When Dan died in 1997, a lawyer in Germany contacted Benny in California and informed him that Dan had no will, so the estate would go to Benny: the half-brother and only relative. He learned that Dan, who worked at the Berlin Police Department, had type 1 diabetes. His possessions consisted of some furniture, clothing, and a few documents in a rental apartment. Benny asked the lawyer to send him the documents and donate the rest of the estate to a local Jewish agency for Russian immigrants. Among the few documents were these bus passes and ID card. No address book, no photos of friends, or anything of that nature to connect him to any other people aside from his parents. But maybe someday I’ll find someone out there.

Chapter 6.6

When I look at this photo of Klara from the early 1970s, I think of a woman who - until her death in 1994 - held onto some shred of hope that she'd one day see her relatives again. I’m not trying to be dramatic or tug at your heartstrings - nearly everyone in Lemberg died - but Klara never had any confirmation of that. No closure. And her niece wasn’t even five years old when she would’ve been sent to the Ghetto with her family. Who knows, maybe the girl could’ve escaped somehow, but didn’t know her family’s name, or was adopted and eventually forgot? Maybe the ITS would send Klara some good news someday? Unfortunately they never found any information on her family members.

I don’t hold out any hope that Betty or Ana or Jacob or Krystyna survived the Holocaust. But I do hope to discover more details about their lives, eventually.

Klara’s resemblance to her brother Reuben (back in Chapter 16) is striking. I wonder if they ever had any contact during the nearly 40 years after WWII when they were both still living. Surely she knew he was alive. The most plausible theory is not a pleasant one: in 1940, Betty received a one-sentence death sentence via telegram: “Son declines furnish funds and prefers mother remain abroad.” That wasn’t the full story, but it was all Betty knew. She and Klara corresponded as late as 1942, so perhaps Klara essentially disowned her brother based on the perception that he abandoned their mother. I doubt I’ll ever know the answer.

Chapter 6.7

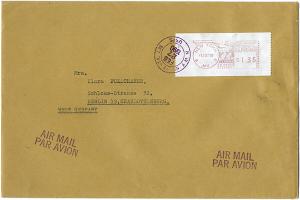

When the lawyer in Berlin sent Dan Fokschaner’s papers to Benny, they included this empty envelope. Before I contacted him, Benny had no idea that Klara was American. And so it was perplexing to him that this envelope was there. Why did she receive mail from New York in 1990?

I think it’s funny that Benny even kept it. It’s just an envelope! It’s empty! But I’m glad he did. To me, it’s evidence that Klara - aged 83 in 1990 - still had some connection to the United States, even though she’d presumably never been back, after leaving as a five-year-old with her parents in 1912. This envelope likely contained something official and mundane - perhaps she’d sent off for a copy of her birth certificate that she needed for whatever reason.

Chapter 34

Last year, in January 2020, my husband Jared and I were in Southern California and we made plans to meet up with Benny. Unfortunately his wife had a cold and couldn’t join, but the three of us had a very nice lunch. It was fascinating to learn about his life as an Israeli Navy diver, engineer, entrepreneur, and world traveler. Making this connection and meeting in person was a pleasantly unexpected result of my whirlwind rabbit hole of a research odyssey that was a dozen years in the making.

This story is not over. Far from it. I have a few leads on research opportunities; once archives and libraries open back up later this year, I’ll start

Chapter 7.2

In the 1970s my grandma Claire wrote down everything she knew about her family. In more recent years, I’ve researched the details and filled in the blanks. This led me to the family of Claire’s cousin Carol: born a year apart, they were close growing up, but Carol was just 26 when she died of peritonitis in 1936. Claire lost touch with Carol’s family, and in 2008 I tracked down Carol’s niece, Helen. That connection is the catalyst that led to everything I wrote in 2021, and everything I’m writing today.

I don’t have a photo of the two women together, but these photos are both from the early 1930s. Carol is the middle left with the headband, and Claire is the middle right.

Chapter 7.2

Slight detour from the story: Helen and I have corresponded periodically over the years since we first met in 2008. When discussing my 2021 story, I said I was going to be a father soon. A few months later a package arrived in the mail: Helen made this impressive quilt for our daughter Chiara. I actually felt a little bad explaining that we were also expecting a son just four months later, because she insisted on making a second quilt! It will be a few more years before the kids understand that their quilts were made by their father’s father’s mother’s mother’s mother’s sister’s son’s daughter, Helen.

Chiara’s Hebrew name is Chaya (???), after my grandmother Claire. In the last story I mentioned that Claire and three of her cousins (Clara, Klara, and Carol) were all named for the same ancestor, Chaya Eisner Landes. And Helen’s sister Cara was named for Carol, so the name ??? has had real staying power in our extended family.

In this photo, Ronen was 1m and Chiara was 5m old.

Chapter 7.3

My grandmother Claire grew up in the company of over fifty cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents. Over the years, the families spread from the Lower East Side to other parts of NYC, other states, and other countries. When I first talked to Helen in 2008, I learned of an entire branch that was missing from my family tree: Claire and Carol’s aunt Betti Landes Wasser and cousin Reuben Wasser. Helen’s family lost touch with Reuben in the 1940s, so I started investigating.

As Americans we hear the stories of immigrants who came here for a better life; most of us never consider "what if some of them didn’t like it, and went back home?" Jacob Wasser became a naturalized American citizen in 1911. Within a year, he and Betti took their three NYC-born children (Reuben, age 8; Klara, 5; Anna, 3) on a 4,500-mile one-way journey to Jacob’s hometown of Lemberg, Austria-Hungary (a.k.a. Lwów/Lvov/Lviv, in modern-day Ukraine).

In 1912 they had another son, Willi Wasser. He was a 21 month-old toddler when Lviv was captured by Russia at the beginning of WWI. The Wassers were just one family among 70,000 Eastern European Jews who fled to Vienna. In 1916 Jacob returned to the US to find a job to support his family. After his unexpected death in 1919, Betti and the children had to rely on relatives in the Wasser family for financial support.

In the 1920s the family applied for passports to return to New York. Betti was informed that her US citizenship derived from her husband’s citizenship, but because she had not filled out some paperwork at a US embassy within a year of his death, she was no longer a citizen. She was not eligible for a passport. Her son Reuben was a legal adult and successfully obtained a passport based on his NYC birth, returning to the US in 1927. Betti and her three other children stayed in Poland.

Chapter 7.4

Making occasional progress over the course of a decade, I learned the fate of the rest of the family, detailed in my 2021 story. Betti, her daughter Anna, son-in-law Jakob, and granddaughter Krystyna were all killed in the Holocaust, either in the Lemberg/Lwów Ghetto, or the Belzec or Janowska camps.

Betti’s son Reuben settled in Maplewood, NJ, later retiring to Florida where he lived until his death in 1982 (his wife Alice died in 1997; they had no children).

The youngest son, Willi, died of tuberculosis in 1931, a month shy of his 19th birthday.

Klara went to Palestine in 1935, married Arnold Fokschaner and had a son Dan in 1949; the family moved to West Berlin in the 1960s. When my husband Jared and I were in Berlin with our kids last summer, we visited their old apartment building and the cemetery where they are buried (Dan died of diabetes in 1997 – age 48 – and his grave is in a different section).

After I wrote their story, I still had questions. There had to be someone out there who knew Klara or her brother Reuben.

Chapter 8.1

A source for my last story was Janet McCabe. Her grandmother was a paternal cousin of Reuben Wasser; my grandmother was a maternal cousin of Reuben. I’m not related to Janet, but when I tracked her down in 2009, she was happy to share memories of our mutual relative. After reconnecting two years ago, she put me in touch with her brother Robert, who might have "a few" letters relevant to my story.

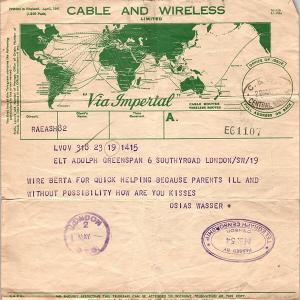

Bob shared this telegram that his great-grandfather Osias Wasser sent from Lviv in 1941. Betti – who also went by Berta – was Osias’s sister-in-law, so maybe this was referring to her…? Bob informed me that it wasn’t just Betti and her daughter's family who stayed in Lviv and were killed in the Holocaust. The victims also included most of Betti’s brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law and nieces and nephews and grandnieces and grandnephews in the Wasser family.

I honestly don’t know what this telegram means. It was sent on May 20th, 1941, when Lviv was occupied by the Soviet Union. Everything was censored, so maybe "quick helping" or "without possibility" were code phrases. And this was the calm before the real storm: just 32 days later, the Nazis executed Operation Barbarossa, turning on the USSR and quickly capturing territory including Lviv in "the largest land offensive in human history, with over 10 million combatants taking part" (Wikipedia). The situation for Jews in the city went from "bad" to "hell" practically overnight.

To find more information on the family’s fate, I would have to look at letters predating this one. I asked Bob if he had other letters relating to Betti or her daughter Klara.

Chapter 8.2

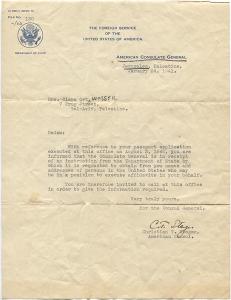

Bob sent me this 1941 letter from the US State Department Consulate General in Jerusalem, which was addressed to "Clara Ort (Wasser)" in Tel Aviv. Why did Bob have this, and where had it been for the last 80 years?! It immediately gave a potential answer to one of my biggest questions: How did Klara Wasser get from Poland to Palestine in the mid-1930s? Apparently she married someone with the surname Ort, and maybe they traveled to Palestine together.

Chapter 8.3

Unfortunately for the purposes of my research, Ort is not just a surname: it’s an acronym. According to Wikipedia, "ORT… also known as the Organisation for Rehabilitation through Training, is a global education network driven by Jewish values" that has been around since 1880. When I checked English and Hebrew records, my search results were all for that organization, not for anyone with the surname Ort. I decided it would be easier to research Polish records, since the Polish language basically doesn’t have any vowels.

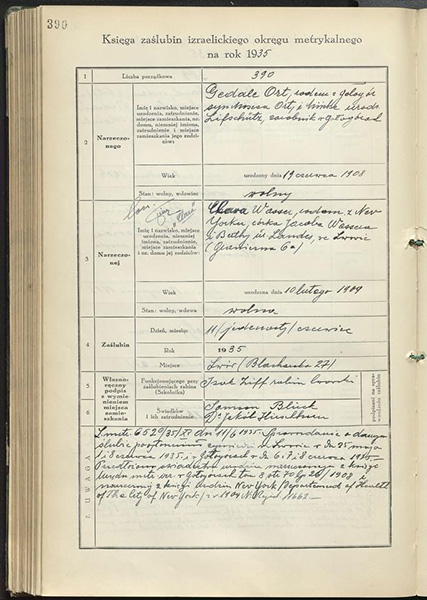

This was early 2021 – pre-vaccine, and, for me, pre-parenthood – so I thought I’d spend some time looking through a few thousand unindexed, handwritten marriage records: every Jewish marriage in Lviv from about 1930-1938. I started my search in the middle. As luck would have it, I found this record within an hour. Klara Wasser married Gedale Ort on June 11, 1935.

Chapter 8.4

Klara Ort (???? ????) and Gedalia Ort (?????? ????) were passengers on the ship "Dacia", arriving in Haifa on August 22, 1935. She is listed on the line 1 about 2/3 down the page, and his name is on another page.

But who was Gedalia Ort? I found that he was from the tiny village of Gologóry, out in the countryside east of Lviv. He first went to Palestine in 1930, at age 20, and became a legal resident. I wondered why he went back to Poland.

His marriage to Klara allowed her to avoid quotas and legally immigrate, immediately. They were married in June of 1935, left for Palestine in August, and divorced in September. How did Klara know Gedalia? Were they friends? No one who knew anything about Klara had ever heard of Gedalia or this marriage, so I went in search of Gedalia’s descendants.

Chapter 8.5

Without Gedalia Ort, perhaps Klara would’ve stayed with her family in Lviv and been killed with all the rest of them in 1942. I wondered if his family knew about this marriage. But it presented a moral quandary: if they didn’t know, would it be inappropriate to inform them? To a lot of people out there, it would not be welcome news that "grandpa had a secret (or fake) marriage he never talked about." On the other hand, regardless of how the arrangement came about, Gedalia Ort saved Klara's life. I decided to reach out to the family. With some persistence over many months, I got in touch with a granddaughter, who wrote:

Gedalia Ort was my grandfather. Talking to my father about Klara Wasser, he was familiar with the story of Gedalia returning to Europe to assist others on their journey to Palestine. He did not recall that any names were ever mentioned, and Klara's name did not ring a bell. In fact, we have no knowledge about how they knew each other nor what happened once Klara arrived in Palestine. Thank you for sharing the marriage record -- it was moving to learn this evidence exists.

Unfortunately, Gedalia lost both his parents and all his siblings during the war. He married my grandmother, Bronia (Reena) and they had three kids, my father, and his twin sisters. Gedalia worked as a Union clerk. After my grandmother's passing in 1991, Gedalia engaged with a community of Russian immigrants. His living room became an informal classroom, where he taught Hebrew to adults who were new to the country and supported them through bureaucratic processes. Gedalia resided in Haifa till his passing in February of 1997.

He was a kind, generous and humble man who deeply cared about and was active within his community.

Chapter 9.1

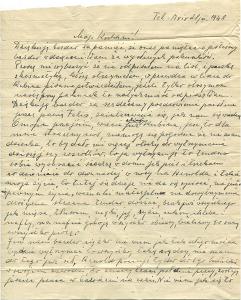

Bob shared this letter that was sent from Tel Aviv in February, 1948. Arnold wrote two pages in German and Klara wrote two pages in Polish; they mailed it to Klara’s brother Reuben in New Jersey. Without even knowing the contents of the letter, one mystery was already solved: Reuben knew that Klara had survived the war, and they kept in touch. The existence of this letter prompted a new question: why did Bob have it?

The letter itself is heartbreaking. Klara writes that life is very hard, there are gunshots everyday, the store shelves are empty, and everything is very expensive. She wants to leave Palestine and go to a place where she can live in peace. She says they will either live in poverty, or "die by the Arab’s knife." Arnold’s letter is below:

Dear Rubin and Alice, Tel Aviv, 9 Feb 1948

It is only today, that I have found the time to write to you. …My dear Klara gave birth to a boy on November 11th… who died in the last few hours of the birthing process. It was a normal child, 3 kilos and 400 grams [7 lb 8 oz], 53 cm long, and the cause of death is unknown. If the doctor had been quicker, maybe everything would have been okay. It was a heavy blow for us and dear Klara is still not okay, it was our big hope, which we had here in this difficult life.

Life is becoming increasingly harder every day and I work night and day and I earn only enough for food… in addition, people are shot every day in the camps and… at night when I return home I go under the bullets of the Arabs, who attack us every night. We do not leave the town under darkness, no car is on the road or if they do, there is no help for peace, not from the police nor the military.

One only has one wish, to live in peace the few years that remain and this is what they won‘t let us do, even here. Nobody knows what will happen and the coming war will probably begin here, judging from the current situation. We only have one wish… to live together a couple of years, in healthy love. I don‘t care… Now my dear, unfortunately our letters are not very enjoyable for you, only worries, but we hope that you are all healthy and okay.

For today I send you heartfelt greetings. Arnold

Hope to hear from you soon

PS: The last attack on Tel Aviv has been survived, both of us still healthy.

Chapter 9.2

Seven weeks later, Klara sent this letter to her cousin in NYC, Janka, who was Bob’s grandmother. Klara thanked Janka for sending care packages of food and supplies. Klara and Arnold were living in the midst of a civil war; just six weeks after this letter, the situation was further enflamed when the Israeli Declaration of Independence became the catalyst for the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Klara wrote about her son who died immediately after childbirth the previous November. "You’ve heard about my misfortune from Rubin. I can’t come to terms with losing my baby, it was a heavy blow to me… A child would give me reassurance that I will survive these living conditions… it’s hard to describe how difficult my life is. I sit at home, like a dog, and wait till midnight for Arnold to come home… I don’t know how much longer we can live like this… I would be the happiest person if Arnold and I could get away from here, alive and in one piece. We would love to experience 'regular life' again and live in peace…"

She asked Janka for a big favor: could she help Klara and Arnold emigrate to the US? This explains why Bob had that 1941 State Department letter addressed to "Klara Ort (Wasser)": Klara sent it to Janka because the American Consulate General in Jerusalem requested "names and addresses of persons in the United States who may be in a position to execute affidavits in your behalf."

Klara's letter closes, "I arrived in Palestine with the name Ort. Within 4 weeks I got divorced, so my surname was always Wasser."

Chapter 9.3

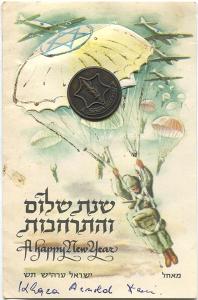

The family never emigrated to the US, but life in Israel improved. In the previous story I wrote about how Klara and Arnold had a son, Dan, in 1949. Klara was 42, and she finally had the child she’d wanted for so long. They sent this letter from Tel Aviv in 1956.

In German, Arnold wrote "thank you for the wonderful package… both suits for me will only need a small change to the pants, they fit my figure very well. I hope that everything is healthy with you, and with your children and grandchildren, they bring joy to life. Many greetings, even though I don't know all of you, your Arnold"

In Polish, Klara wrote "Don’t be mad at me for not responding to your letter sooner; the reason is that life here is hard, and we need strong nerves to survive. We are very grateful for the package; it has arrived in one piece, Dani is thankful, and it was very tasty, he is asking when auntie Janka will come visit us. Soon I’ll send you, my loves, pictures of Dan from the Purim performance in school, it was nice.

…Do you know what is happening with Jadzia - how is she doing? How are you doing, health-wise? Is everything okay? Where do your kids live? Close to you? I remember Stefan as a 6 year-old little boy. I will try to write to Rubin and send a photo of Dan.

Once again, thank you very much for thinking about me. I am sending you warm kisses. Yours, Klara"

In Hebrew, Dan wrote: "Shalom, Aunt. I am very happy and thanks much for the clothing. Shalom. Dani."

Chapter 9.4

The several letters from Klara and Arnold that Bob sent me were incredibly helpful in learning about their lives during that period. I figured I’d exhausted all reasonable paths of research, but then I remembered something that Arnold’s biological son Benny once mentioned. Arnold had a brother named Rafael who also emigrated from Berlin to Palestine in the 1930s. Maybe Klara was close with her in-laws? Benny hadn’t been in touch with them in over fifty years, so I’d have to find them on my own.

I came across this 1933 Berlin marriage record of Felix Fokschaner and Lieselotte Hirschberg. Between the Fraktur font and Sütterlin and Kurrent styles of handwriting, old German documents are notoriously difficult to read; it’s ironic that Arnold’s signature – in his terrible handwriting – is nearly the most legible part of this document. Regardless, this document didn’t help my search. It only introduced another given name for Arnold’s brother: was he Felix or Rafael? And surely the wife didn’t go by Lieselotte after emigrating to Israel.

Chapter 9.5

By this point you know that I’m stubbornly persistent. With some effort, I found that Rafael and Lea Fokschaner changed their surname from Fokschaner to Perach (???, which means "flower"), and had four children. I emailed their granddaughter, Orit, who sent me this photo of her grandfather Rafael and his brother Arnold.

I asked Orit if she knew her great-aunt Klara, and she wrote:

"I knew Klara as she stayed in our home for a while when she visited Israel when I was a young girl. I don't remember the circumstances but she was alone as it was after Arnold passed away already.. I didn't know Arnold nor Dani. Just heard of them from my mother and father. My mother knew them well."

Arnold, Rafael, their mother, and their respective wives emigrated from Germany to Palestine together. They went "with other German Jews to a Kibbutz 'Gesher' and there they established a core group for starting a new Kibbutz not far from there, both are in Emek Israel which is in the northern part of Israel. My father was born on Oct 1934 and was the first baby of that new establishment called later as 'Ashdot Yaakov'. Indeed it was hard weather and conditions, and Arnold and Lily left to live in Tel Aviv city."

Orit's mother "was the history person in our family, wrote and kept all letters but to my sorrow she does not remember much now. She visited Arnold and Klara in Yad Eliyahu which is Tel Aviv neighborhood and took care of Danny several times. Klara stayed in our house at the time for several weeks… The life in Israel was hard and as I understand this is the reason Klara and Arnold left Israel. My Grandfather didn't find himself very well in the Kibbutz in Emek Israel (very very hot and hard) where they went when they came to IL in 1934. He had depression and eventually tried to kill himself. Well – when digging you find not what you wish to find."

Chapter 9.6

I was very glad to get in touch with Orit and learn about Rafael’s family. Her family’s oral history complements Klara’s letters to Janka; the narrative of an incredibly difficult life during the British Mandate period and the early days of Israel’s independence is important for us to remember. Klara left Poland (where virtually all her relatives were later murdered) and tried her best to make a normal life and have a family in a very undeveloped place in the desert, full of civil strife. She never had it easy.

This unusual 1950s New Year's card is the last correspondence that Bob could find among his grandmother’s papers. I don’t know what life was like for Klara, Arnold, and Dan after they moved to West Berlin in the 1960s. Maybe someday I’ll find someone who knew Dan.

At the same time, I’m very mindful of any person’s "right to be forgotten." I always make a conscientious effort to tell people, "you knew this person. Do you think they would be ok with me preserving and sharing this information?" For her part, Orit wrote:

"Of course you can use our correspondence for your story, it's fascinating and helped me learn things about my origins as well. If you come to IL please let me know, we have to meet." I hope we will, someday!

Chapter 10.1

I need to introduce Julia. Soon after Bob started sending me Polish letters, I asked for translation assistance on a Jewish genealogy Facebook group, and Julia offered to help. It was the beginning of a great friendship and collaborative research effort (I don’t know how she has time for our work when she’s simultaneously doing her radiology residency and completing a PhD to complement her M.D.).

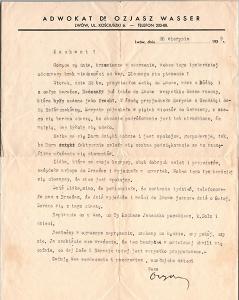

One of the first things I asked her to translate was this letter. Betti’s brother-in-law Ozjasz (Osias) Wasser sent it to his daughter Janka on August 28th, 1939; Poland was invaded by the Nazis and the USSR on September 1st. Given the date, I wondered what it might say. I was unprepared for the last few sentences of the letter, which give me shivers every time I read them:

Lviv, 28th of August 1939

Lovely!

The days are hot, full of events, so we feel all the more the lack of news from you. Why don't you write?

On Tuesday the 22nd I drove Mother, Rózia and all the luggage to Lviv. All your belongings, which were shipped as freight, have also arrived in Lviv. On Wednesday Maria arrived with Wanda and little Holówczakówna arrived. Maria went to Warsaw on Friday evening, which I am very happy about, because currently traveling is so difficult that I doubt whether it would be successful. Mother is doing well, thanks to God, she is calm, she manages the house; yes, God really deserves a separate thank you for this positive outcome.

…Please write to us, what are you up to my dear Janeczka, my dear Dol and children?

We are in great tension, waiting to see what will happen, whether there is going to be peace or not. I have a feeling that this bandit will back out of it at the last moment, so help us God! As for now, everything here is prepared.

Kisses and greetings, kisses for children.

Yours,

Ozjasz

Chapter 10.2

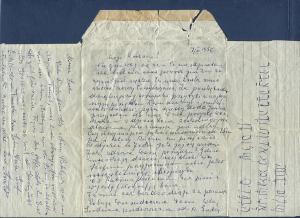

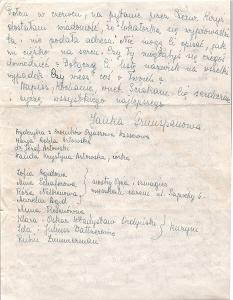

This is page 2 of another letter Bob sent; the list of family members stood out to me. In September 1945, Bob’s grandmother Janka mailed it from NYC to her friend Anna Feygl in Prague. After reading it, Julia and I were intrigued, and we wanted to learn more about this family that neither of us are even related to. I started filling in the blanks on Bob’s incomplete family tree. Part of Julia's translation of this letter is below:

Dear Anna!

I’ve found your name on the list of people released from Theresienstadt… so I’m sending this letter to your old address. Maybe you will receive this letter. Please, Love, write back to me immediately, is there anything you need?

…I haven’t heard from our family, from home. The last postcard I received from my Mother was in March 1942. She wrote: "Father is dead, Jurek (Marysia’s husband) is no longer with us. Me, Marysia and Wandzia (Marysia’s younger daughter) are poor and abandoned." The return address was ul. Panienska 40, which was in the Ghetto.

In June, I asked the Red Cross - they responded that "the people at that address moved out. Their current address is unknown." You can’t imagine how difficult this situation is for me. Would you be so kind and try to learn more for me? Below, I’m attaching the list of people I’m looking for. Do you have any information about your family?

Please, write to me, Love. Hugs and best wishes.

Janka Grunspan

[she included a list of fifteen missing relatives]

Chapter 10.3

Anna’s response to Janka is below:

October 5th, 1945.

Dear Jancia!

Your card from July the 4th reached me at October the 4th – and I was quite surprised that it reached me at all! It was sent from Stockholm to Terezín (Theresienstadt), where I was actually living from January 1942 till July 1945. From Terezín it was sent to Prague to my present address: Praha II, Lublanská 43.

…About your family in Poland I unfortunately can not give you any news. Only about your father, if you still do now know it: my mother wrote me… that he died suddenly, from a heart apoplexy. I guess it was spring 1941. He could not have been very ill before, because he often visited my mother. Later I heard nothing more about them. I myself had news from my mother till August 1942 – then suddenly "The addressee went away, unknown where." From this time I never more heard anything from or about somebody from my family, or from Lvov generally, although you must believe that I tried hard enough.

All I learned from Polish people returning from the Concentration Camps through Terezín was: from the East-Poland Jews, do not wait for anybody, they are nearly all dead. From the West-Polish Jews, the younger and stronger ones are partly alive – but I never met somebody from Lvov. I myself have no hope at all, for nobody from my family. My husband died January 1945 in a Concentration Camp in Germany.

I am very sorry to give you such sad news – but I think that you cannot be unprepared for them! Can you please tell me what became of the things I sent you in May 1939? I would be very glad to have them now, especially the fur, as I have nothing warm to put on. How could I get it back?

I am working as a physician in consultations for mothers and children, live in one furnished room, and sometimes ask myself, what for did I survive to all that? But perhaps I may know it, one day. In the meantime I kiss you very affectionately and wait for your answer.

My love to your family! Yours Niuta.

Chapter 10.4

Jared says my stories are too depressing, so here’s a picture of babies. Last summer in Prague we went to Anna Feygl’s 1945 address: Praha II, Lublanská 43.

To find a little more detail about Anna’s life, I contacted Šimon Krýsl, head of the National Medical Library Medical Museum in Prague. He was gracious enough to do some research for me, and he wrote a short bio of Anna:

Paediatrician, studied in Lemberg and at the German University in Prague (graduated June 25, 1927), after graduation an externist at the II. Children Clinic (German University), 1930-1940 specialist practice in paediatry in Prague. On June 30, 1942 deported to Theresienstadt, where she worked as doctor in the Säuglingsheim; in 1946 she restarted her practice in Prague. In the post-war years she published both scientific and popular articles and books on paediatrics and translated into and from Polish.

Chapter 11.1

In our early correspondence I asked Bob how many more of these old letters he had. His responses were cagey, which I chalked up to a reluctance to turn over his family’s history to a stranger. Through emails and calls we quickly got to know each other. I suggested that if he wanted to send me some old letters, I’d scan them and see if I could find anyone to translate them.

I eventually learned that Bob’s grandmother Janka saved every scrap of paper – including actual, tiny scraps of paper – relating to her missing family members, totaling around 500 pages. Bob hadn’t been cagey about the quantity because of privacy concerns; he'd held back because he didn’t want to scare me away.

About 60% of the letters are in Polish, 25% in German, and the rest are English, French, Spanish, or Hebrew (plus several documents in Czech, Russian, or Ukrainian). It’s impressive that his grandparents were such polyglots; it also means that there are very few individuals in the entire world who would be able to read all of these papers. I’d have to assemble a team.

Chapter 11.2

I asked Bob how he ended up with the ~500 pages of letters saved by his grandmother. He told me a story that galvanized my growing sense that this was a task – a mission – a massive project – that I had to take on. It went something like this:

"When my elderly mother moved out of her house, we found her parents’ collection of letters in a box in the attic. I asked Mom what she wanted to do with them, and said I was happy to take them if she didn’t want them. She said ‘well, I suppose you can.’"

She had already kept the letters for all these decades after her own parents had passed away. Perhaps she reached a point where she thought, "they’ve served no purpose to anyone for this long, so why keep holding onto them?"

Bob is a collector of all things old. He took the box home and went through the contents. He quickly realized that the box contained a treasure trove of letters documenting the tragic exodus of the members of his mother’s family who fled Europe in the 1930s — and those who didn’t make it out. A challenge to further discovery was that most of the letters were not in English. He flattened out and organized the letters, put the fragile old pages in plastic sleeves, and even made photocopies of some letters to send to his two elderly uncles who knew some German, Polish, Spanish, and French. They wrote a few summaries of the letters' very depressing contents, and then Bob put the plastic-sleeved letters into binders, the binders into plastic tubs, and the tubs into the basement storage unit of his Manhattan apartment building. There they sat, for a decade or so, until I inquired.

From this photo, you will appreciate the fortunate series of events that led to the preservation of these letters. They should have disintegrated half a century ago.

I’ve scanned and labeled every last scrap of paper, and I’m obtaining transcriptions and translations of them all. I’ve gathered well over a thousand pages of other documents – and four unpublished memoirs – during the last two years. I also managed to track down a couple dozen people all over the world who have a connection to these letters, collecting their sides of the story.

I have a confession to make: I haven’t even begun the story I set out to write today. This is just the prologue ??